We love revision…right?

Revision – it really matters. But, with the best will in the world, it’s not the most exciting way to spend your time. The process itself requires you to look back at work you’ve already done – to “re-vision” it – to try and remember it and commit it to memory. There’s nothing “new” in it. But the trick to making it effective is to get your brain working as hard as it can be.

The reason for this is best summed up by cognitive psychologist Daniel Willingham. Willingham says:

Whatever you think about, that’s what you remember. Memory is the residue of thought.

In other words, you need your brain to really be processing the information you are trying to revise, if you want to stand any chance of remembering it.

What doesn’t work?

There are a few techniques that seem effective – but actually aren’t. These include:

- Highlighting

- Re-reading

- Summarising

Highlighting: expectation vs reality

These techniques allow information to pass through your brain without much thinking. Covering pages of A4 with beautifully highlighted patches might make you feel like you’ve achieved something, but it won’t actually help you to remember the information. These are low challenge activities, and therefore low impact

What does work?

Practice Testing

This technique is pretty straightforward – keep testing yourself (or each other) on what you have got to learn. This technique has been shown to have the highest impact in terms of supporting student learning. Some ways in which you can do this easily:

- Create some flashcards, with questions on one side and answers on the other – and keep testing yourself.

- Work through past exam papers – many can be acquired through exam board websites.

- Simply quiz each other (or yourself) on key bits of information.

- Create ‘fill the gap’ exercises for you and a friend to complete.

- Create multiple choice quizzes for friends to complete.

Distributed Practice

The Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve – if you revisit newly learned information, you remember more of it

Rather than cramming all of your revision for each subject into one block, it’s better to space it out – from now, through to the exams. Why is this better? Bizarrely, because it gives you some forgetting time. This means that when you come back to it a few weeks later, you will have to think harder, which actually helps you to remember it. Furthermore, the more frequently you come back to a topic, the better you remember it.

Elaborate Interrogation

One of the best things that you can do (either to yourself or with a friend) to support your revision is to ask why an idea or concept is true – and then answer that why question. For example:

- In science, increasing the temperature can increase the rate of a chemical reaction….why?

- In geography, the leisure industry in British seaside towns like Porthcawl in South Wales has deteriorated in the last 4 decades….why?

- In history, the 1929 American stock exchange collapsed. This supported Hitler’s rise to power….why?

So, rather than just try to learn facts or ideas, ask yourself why they are true.

Self explanation

Rather than looking at different topics from a subject in isolation, try to think about how this new information is related to what you know already. This is where mind- maps might come in useful – but the process of producing the mind map is probably more useful than the finished product. So, think about a key central idea (the middle of the mind map) and then how new material, builds on the existing knowledge in the middle.

Alongside this, when you solve a problem e.g. in maths, explain to someone the steps you took to solve the problem. This can be applied to a whole range of subjects.

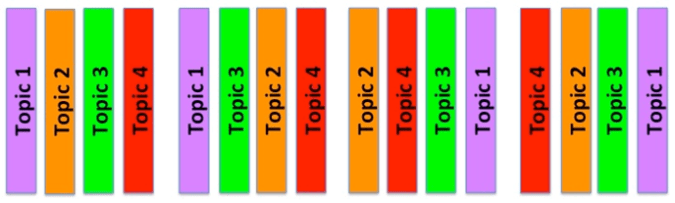

Interleaved revision

When you are revising a subject, the temptation is to do it in ‘blocks’ of topics. Like this:

The problem with this is, is that it doesn’t support the importance of repetition – which is so important to learning (see distributed practice above!) So rather than revising in ‘topic blocks’ it’s better to chunk these topics up in your revision programme and interleave them:

This means that you keep coming back to the topics. So, instead of doing a one hour block of revision on topic 1, do 15 minutes on topic 1, then 15 minutes on topic 2, then the same for topic 3 and 4. The next day, do the same. On day three – just to spice it up and stop your brain getting into a rut – mix up the topics!

Have a break

Your brain can only work effectively for so long. Scientists differ on this – some say our attention span is around 20 minutes, whilst others say we can work for longer. My advice is to revise in blocks of around 45 minutes, giving yourself a 15 minute break in each hour to recharge. Make sure you get some fresh air, relax and switch off. You don’t want to underachieve because you haven’t done enough revision – but equally, you need to stay healthy and happy if you’re going to do your best, so don’t overdo it!

Resources

There are lots of resources out there to help you revise. Here are just a few:

- Get Revising study planner

- Helping your child revise 2016 guide for families

- Memrise especially for Languages

- MyMaths and Maths Genie – for Maths!

- BBC Bitesize GCSE – all subjects

Good luck!

With thanks to Shaun Allison for the inspiration and some of the images for this blog. Read Shaun’s original post here.